Day 6: Peer effects

A series following my new class: The Economics of Higher Education

So sorry for the delay, it’s been a doozy of a week over here! My oldest kid was out of school sick for two days and our oldest dog needed emergency stiches after getting tangled up in something in the backyard, all while my husband was out of town and I’m teaching a new prep on the Block Plan. Doozy.

Anyway, we’re back! Today reporting on Day 6, second Monday of the 3.5 week block. On the agenda: peer effects.

But first, an update on Day 4: The Returns to Higher Education: a friend wrote to say that I really need to put some different papers on my syllabus next year. And I think that’s awesome! That’s precisely why I’m writing this Substack, so I can get you all to do some of my work for me. My friend suggests you all should read:

Ost, B., Pan, W., & Webber, D. (2018). The returns to college persistence for marginal students: Regression discontinuity evidence from university dismissal policies. Journal of Labor Economics, 36(3), 779-805.

Zimmerman, S. D. (2014). The returns to college admission for academically marginal students. Journal of Labor Economics, 32(4), 711-754.

Bleemer, Z., & Mehta, A. (2022). Will studying economics make you rich? A regression discontinuity analysis of the returns to college major. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 14(2), 1-22.

Please keep the updates and suggestions coming!

Today’s readings

Winston, G. C. (1999). Subsidies, hierarchy and peers: The awkward economics of higher education. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 13(1), 13-36.

Carrell, S. E., Fullerton, R. L., & West, J. E. (2009). Does your cohort matter? Measuring peer effects in college achievement. Journal of Labor Economics, 27(3), 439-464.

Winston, G. C. (1999). Subsidies, hierarchy and peers: The awkward economics of higher education. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 13(1), 13-36.

Higher education is an odd industry for many reasons, but the biggest one is that its customers are also an important input in production. Meaning, good students will pay more for your education if it’s high quality, but peer interaction is an essential component of a high quality education so you need good students to start with so you can attract the good students. It’s a loop. A self-reinforcing loop.

Because peer effects are such an essential component in the production of higher education, institutes of higher education have an incentive to subsidize good students, i.e. offer them educational services at a discount from what it actually costs to produce those educational services. That’s how you attract the highest quality students, which then attracts more high quality students, and so on. That’s how you make the loop work for you.

Your first thought is probably that students get grants because of financial need (i.e. their families don’t make enough money to pay for the full cost of college). That’s true, and we’ll talk about need-based financial aid in more detail on Day 12. As a preview, this article presents summary statistics about the average student subsidy/discount (column 2), actual cost of education (column 3), price net of subsidy/discount (column 4), and the percentage of price actually paid by students (column 5) for schools in 1995. This table also splits schools up by wealth of school, starting with very wealthy schools (Decile 1) on down to not very wealth schools (Decile 10). While it’s clear that wealthier schools offered higher subsidies, even the least wealthy schools (those in Decile 10) were offering some subsidy/discount to students.

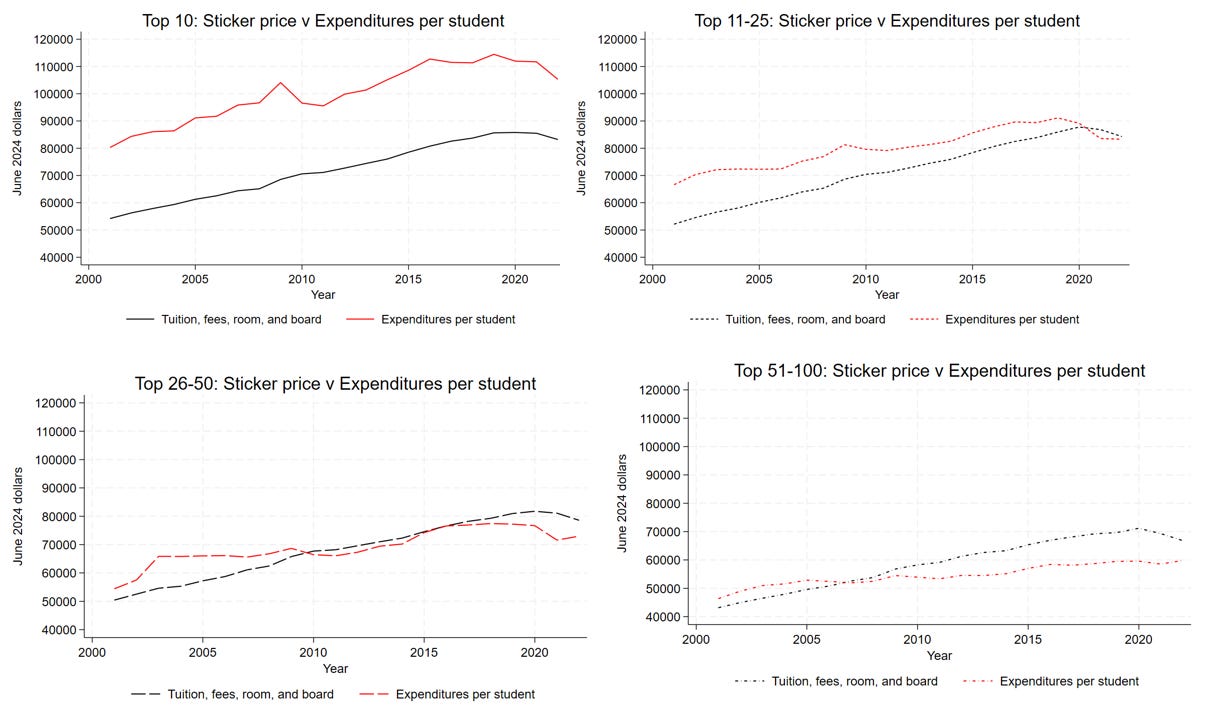

What you may not know is that for many schools for many years, ALL students paid less than the full cost of their education, even students paying the full sticker price. I wrote about this in a previous Substack post; the money chart is below. These charts show information for the top 100 liberal arts colleges for the years 2000-2023. You can see that the top 10 liberal arts colleges (the top left figure) are spending approximately $20,000 per student more than their full price tuition, fees, room, and board (a.k.a. the sticker price). Schools in the top 11-25 slots (top right) were spending $15k more per student than the sticker price in the early 2000s (in constant 2024 dollars, i.e. adjusted for inflation terms), but since 2020 are spending about equal to the sticker price. The switch point for schools in the Top 26-50 range (bottom left) switched over charging full-pays more than their average expenditures per student around 2009, while schools in the 50-100 range (bottom right) switched around 2007.

Why would a school charge less than it costs to produce their product? Why do they subsidize even rich students and families? They’re making the peer effects loop work for them.

Wealthy schools pay a subsidy to all students because the existence of that subsidy pushes demand up above supply; this excess demand allows wealthy schools to be choosy about who they admit; this selectivity then pushes the average student quality up, which in turn increases demand. Schools that are able to select for high student quality can then employ different production and teaching techniques, namely those that rely on high quality peer effects. Small classes, residential college, peers of the same age, no online classes, etc. The concentration of high quality students and high intensity production techniques is in turn related to better post-graduate incomes and outcomes, thereby increasing donations. Larger endowments then afford the possibility of offering larger subsidies to future students, and so on and so forth forever. It is precisely this feedback loop that generates hierarchy in higher education.

But hold on a sec. This whole notion of an upward spiral depends on the notion that high quality students attract other high quality students because high quality peers make you learn more in school. Is that actually true?

Carrell, S. E., Fullerton, R. L., & West, J. E. (2009). Does your cohort matter? Measuring peer effects in college achievement. Journal of Labor Economics, 27(3), 439-464.

There are usually two big hurdles to measuring how a person’s peers affect their own outcomes. First, my peers affect me and I affect my peers. Charles Manski describes this as the “reflection problem;” I really like that name for it. Second, people usually choose the peers they hang out with, by choosing what classes to take, who to study with, which professors to seek out, where to live, etc. This we’ll call the “selection problem.” It’s usually difficult to impossible to overcome both the reflection and selection problems in one setting. But luckily this paper presents essentially the perfect setting for measuring peer effects in higher education.

The researchers have a ton of information about each student before they arrive at college, including their high school GPA, SAT scores, physical fitness score, measure of leadership aptitude, and a standardized intelligence test. They can use this pre-college information as a measure of student quality before they engage with peers, thus getting around the “reflection problem.”

Students are randomly assigned to dorms, rooms, and social groups. All students take the same classes and their schedule is assigned, not chosen. This gets us around the “selection problem.”

Students take the exact same exams at the end of each class so the scores are truly comparable across students. This isn’t a must-have, but it sure is nice.

There are enough people in the study and sufficient variation in average pre-college characteristics between randomly assigned groups to generate enough statistical power to actually see any effects.

Where is this magical place? The United States Air Force Academy! Just up the road from me.

USAFA is an additionally great place to study peer effects in higher education because while other studies examine how changing a roommate or dormmates affects a student, USAFA randomly assigns a student’s entire peer group. Cadets are assigned to cadet wings of 4000 students across all class years, and smaller squadrons within that group too. Cadets are required to spend most of their time with the other cadets in their wing and squadron. This set-up allows us to ask the question “what if a first-year college student’s entire peer group were a bit better?” not just “what if a first-year college student’s roommate were a bit better?” This is much closer to what would actually happen if a college were to adjust their admission policies whole scale, and gives us the best chance of observing peer effects because the effects of changing whole peer groups is probably bigger than changing just a few dormmates.

What do they find? When a new cadet is assigned to the squad with the highest average SAT verbal score (666) instead of the lowest average SAT verbal score (606), that cadet’s first year course grades increase by 0.24 points. The average grade in a first year course is 2.91 (no grade inflation there!) so moving from the lowest squad to the highest squad would increase a cadet’s typical grade from a C+ to a B-. In the education literature, we think of a standardized effect size of 0.05 as small, 0.1 as medium, 0.2 as big, and 0.4 as really big. This is a 0.05 standardized effect (a 1 standard deviation increase in peer SAT verbal scores leads to a 0.05 standard deviation increase in own first-year grades).

The effects are largest in classes with lots of opportunity for study partnerships and smallest in classes with the least student interaction, suggesting that this is a human capital building/actually studying story, not a social norm/anything-you-can-do-I-can-do-better story. The effects of a cadet’s first year peers persist (but are diminished) through senior year GPA. The effects are largest for cadets who come in with the lowest scores in high school.

This study is so cool! And kind of a bummer too. This is the best possible set-up we have to measure the effects of peers on academic achievement, and while the effects are statistically significant, they’re also kinda small. But then again, maybe we should care less about GPA as an outcome of peer effects. So say my students anyway…

Special note: I knew one of the authors of this paper. Rich Fullerton. Rich was a visiting professor at Colorado College when I first joined in 2015. He died in December 2016 of a heart attack. He was 55. Rich was a retired Air Force Brigadier General, had lived all over the world with his wife and three kids, and cared deeply about his family, his faith, our country, and our students. Rich was one of the kindest people I’ve ever known, and I miss him regularly.

Student discussion

On Day 5 we talked a lot about how this group of students values education because of the conversations, personal growth, discipline, teamwork, and people skills they’ve learned through college. They care a lot less about the technical knowledge and skills that are proxied by things like GPA, so it was hard to get some of them interested in the results from the Carrell et al. paper. GPA just doesn’t feel all that relevant to some of them. Because it’s the soft skills they really value, maybe they want a large range of student abilities. Maybe they actually want some students with low SAT scores and bad high school GPAs precisely because it adds to the diversity of people they encounter in college. Besides, test scores and GPA only measure some kinds of ability, they point out, and there are plenty of students who are good peers in the classroom and in co-curriculars/athletics who totally bombed formal metrics of success in high school.

Some of my students this block really believe that John Rohn saying that you are the average of the 5 people you spend the most time with, so it’s super important to choose your peers carefully. Others thought that they were more independent than that, so they were seeking a wider array and diversity of peers they wanted to be around.

We then talked a bit about the portfolio of students a college might select. You might want some tried and true good grades kids, and maybe you take some risks on applicants with a few Ds on their transcripts. But if the whole portfolio was students with a lot of Ds, well that wouldn’t be a great peer group. We also talked about how to take risks at different stages of the admissions process. Early Decision admits are almost certain to come, while Regular Decision admits are much less likely to accept. So maybe you should select the tried and true good grades kids from the ED pool, and take more gambles in the RD pool. (How does the Admissions Office craft a class? Well wouldn’t cha know, that’s who we’re talking to on Day 7!)

We ended by talking about how much and what kind of manipulation colleges should do in their first year classes/programs. At CC, all first-year students take two required first year courses, the first in their first month of college and the second sometime later in the first semester. And of course first year students are assigned to roommates and dormmates. Should we want all similar or all different students in these peer groups? Should they be designed to maximize follow-on GPAs or to encourage mixing of different types of students early in the college experience? This conversation makes me think that next year, I should invite the Director of the First Year Program to join our class on this day.

How does the Admissions Office select a class? How much does it really matter which college you go to? And given all the competition for spots at elite schools, how have high schoolers adapted to improve their chances of admission?

Those are the topics of conversation up next on Day 7: Admissions.

That is a very kind and sweet tribute to Brig General Fullerton💔