Why the increase in adjuncts and leftie administrators might be related

Higher education has critics on all sides these days.

Faculty have lots of complaints, and one of them is the “adjuntification” of higher-ed. More classes are taught by professors on temporary contracts which, the permanent faculty worry, leads to tenure-track faculty losing power to the (neoliberal/capitalist shill/corporate overlord) administration.

People who lean right politically complain that most faculty and administrators are too left leaning. Too many Marxists. So many communists. This, they bellow, was caused by leftie capture of all of America’s great institutions.

I think it’s funny that faculty think the administration is too right while much of the public thinks higher-ed administration is too left.

And I wonder if both phenomena can be explained (at least in part) by something much more boring: a mismatch between the supply and demand of different types of skills.

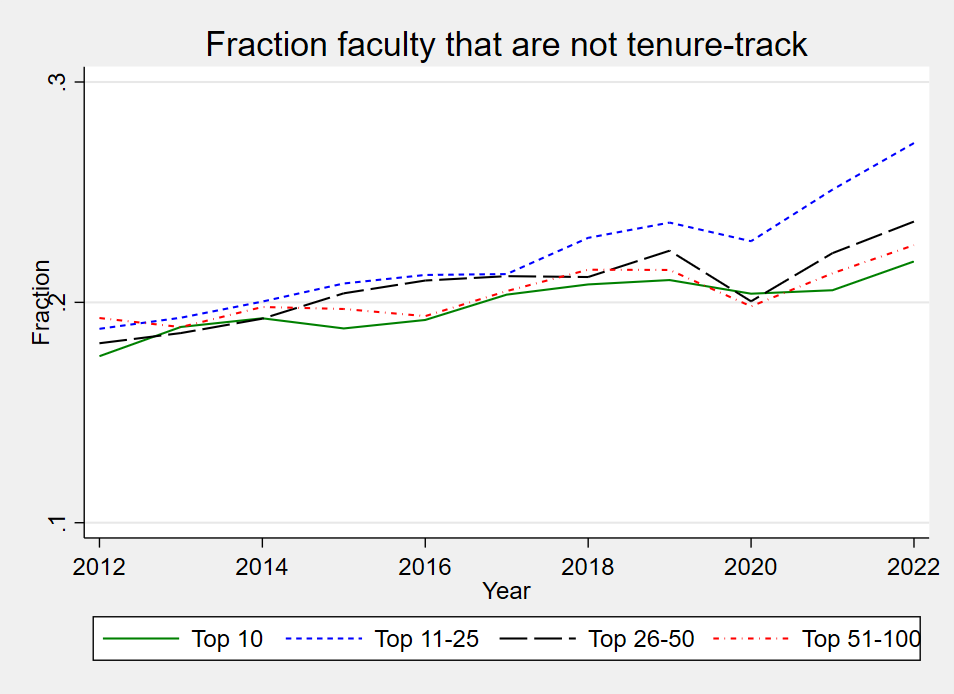

First off, it’s true that the fraction of faculty that are on temporary contracts has increased, even at liberal arts colleges. The chart below shows data from the Employees by Assigned Position dataset in IPEDS.1 The fraction of full-time professors who were not on the tenure track (i.e. adjuncts, lecturers, instructors, professors of practice, visiting professors, etc.) increased from 18.6% in 2012 to 23.8% in 2022. The chart also shows that this shift occurred everywhere, regardless of USNWR ranking.

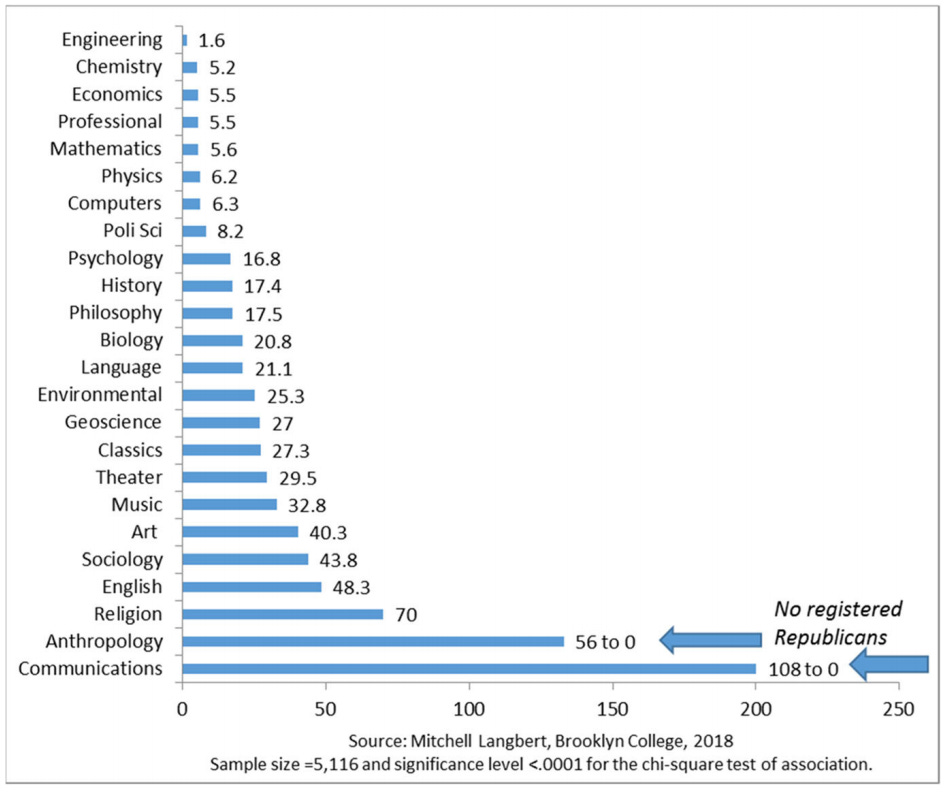

Next, I’ve read credible reports that faculty members lean Democrat, and that the lean is stronger for some disciplines. For example, this piece by Mitchell Langbert (Associate Professor of Business at Brooklyn College) gathered the official party registrations of 8688 tenure-track faculty at 51 top liberal arts colleges in 2017. He finds that the ratio of registered Democrats to registered Republicans is higher in the humanities and some social sciences and lower in the natural sciences, economics, and professional fields like business; notably, the ratio of registered Democrats to registered Republicans is higher than 1 to 1 in every field.2

I don’t think I’ve seen great reports on the political affiliations of administrators, so just for fun, I looked up the fields of all of the Chief Academic Officers of the schools in my sample. These are your Deans of Faculty, Provosts, Deans of College, etc. 41% came from a humanities background, 33% came from the social sciences, and 26% came from the natural sciences.

So yeah, faculty and administrators lean left. (Also, have you met us? This is obviously true.)

“Adjunctification” is definitely happening, to the dismay of the lefties.

Administrators are often lefties, to the appall of the righties.

But are these things necessarily happening for nefarious reasons? And could they possibly be related?

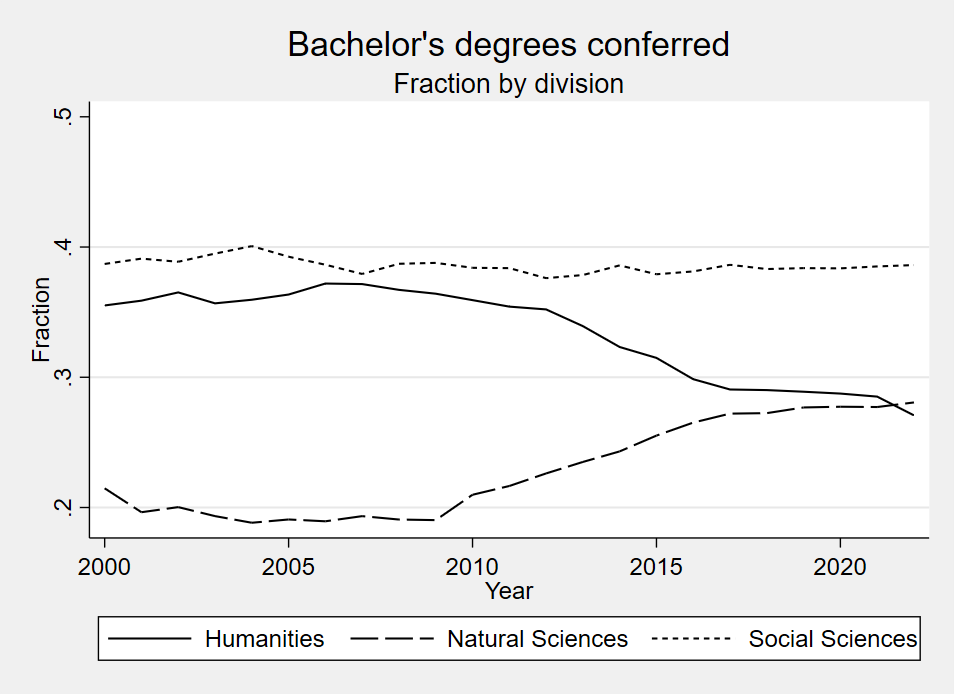

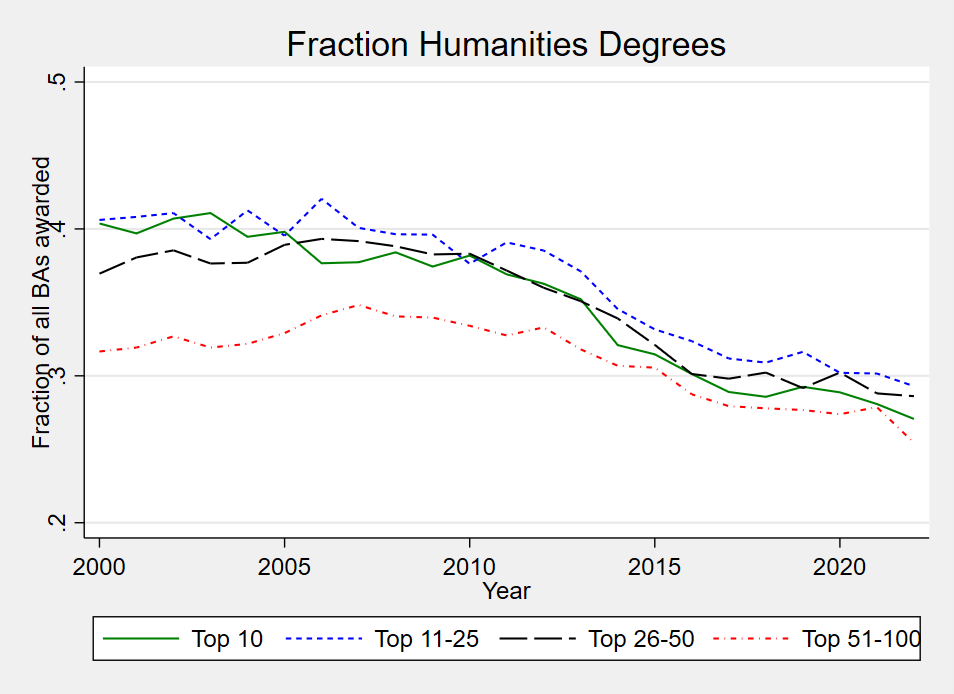

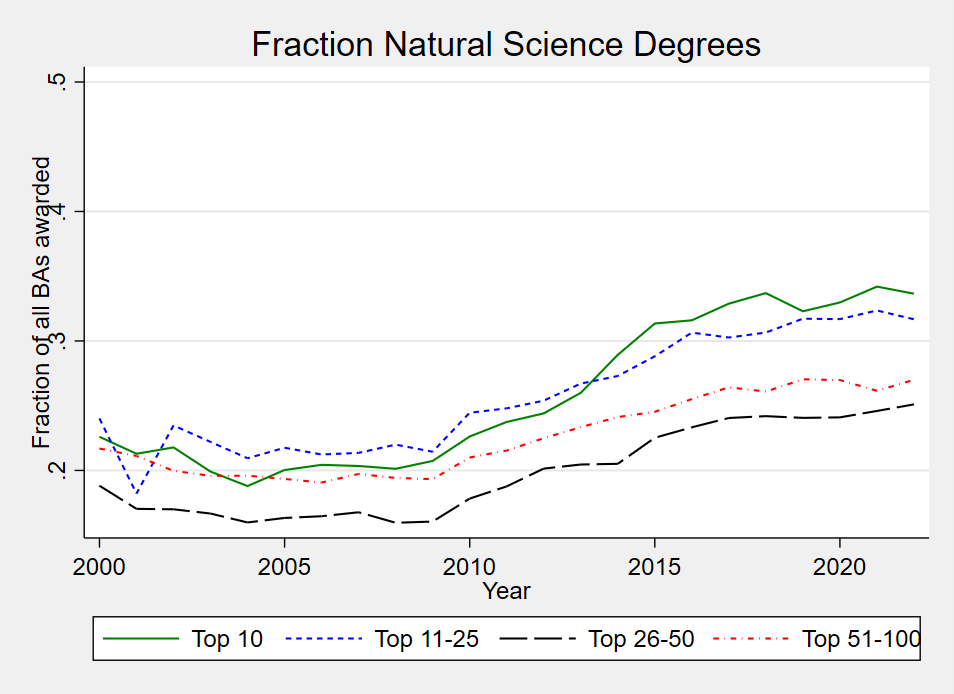

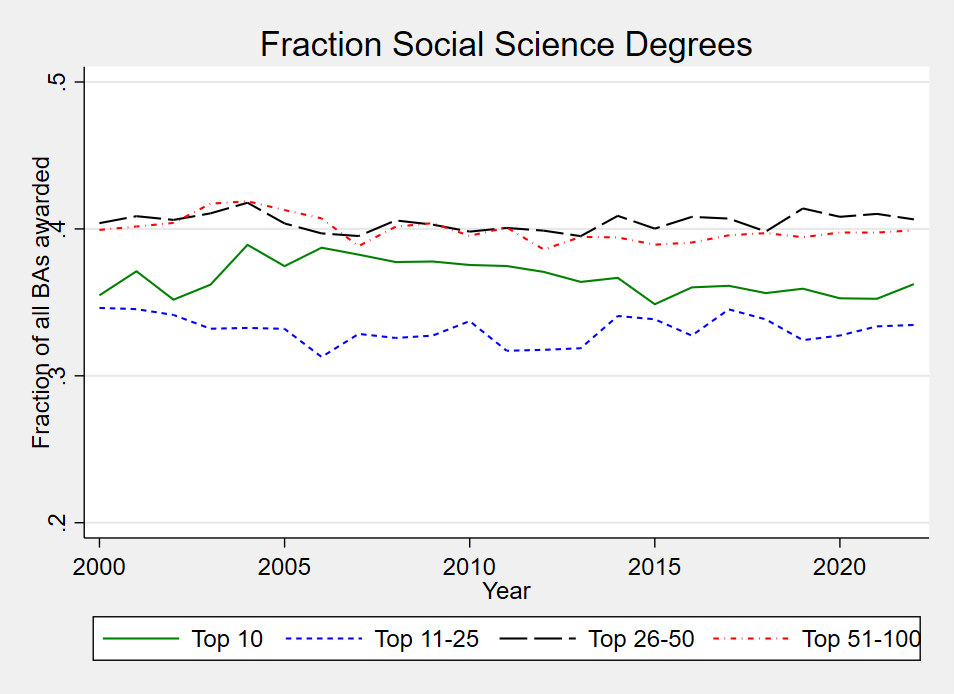

You may have heard that student demand for humanities degrees fell a lot since the Great Recession of 2008. That’s true, even at liberal arts colleges. The chart below shows the fraction of total bachelor’s degrees awarded at the top 100 liberal arts colleges by academic division over the last 20 years. For this I used data from IPEDS’ Completions datasets. You can see that the fraction of degrees conferred in humanities fell from 35.5% to 27.0% from 2000 to 2022, while the fraction in the natural sciences rose from 21.5% to 28.1%; social science degrees held steady at about 38-39%. If you’re interested, I put some extra charts in the footnotes that show the trends across the 4 tiers of schools by USNWR ranking.3 These trends hold across the industry, though there are different levels by tier.

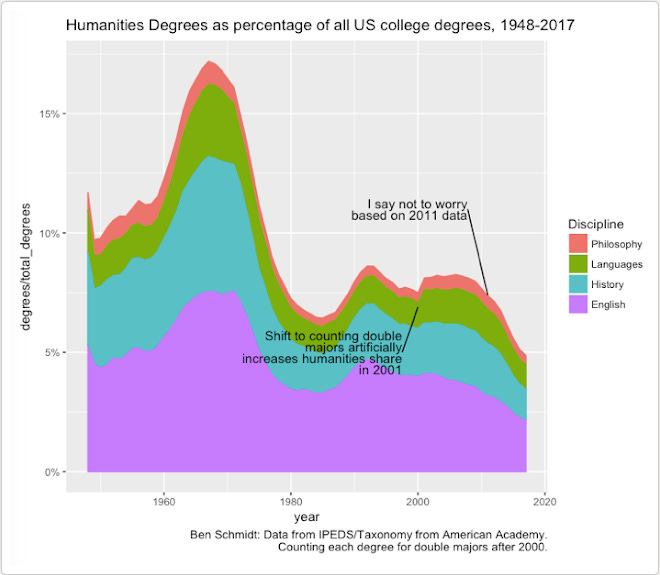

What you may not know is that the drop in humanities degrees after 2008 was not the biggest change in recent history. There was a huge increase in the share of humanities degrees from the early 1950s to late 60s, followed by an even larger drop from the late 60s to the early 80s, and a mild rebound from the mid 80s to early 1990s. Demand then held steady until the crash starting in 2008. This plot shows the fraction of degrees conferred in humanities from all US colleges from 1945-2017. It’s from a blog post by Benjamin Schmidt (now VP of Information Design at Nomic and previously Assistant Professor of History at Northeastern University) that turned into an Atlantic article (free link here) about the more recent crisis in humanities.

Think for a moment about how this affected who has been in the professoriate over time. The two longest serving members of my faculty joined the college in 1965 (no, that’s not a typo; yes, they are still teaching). The third longest serving joined in 1967. Another prominent long-timer arrived in 1970. Three are in the humanities, the other in social science. They were hired at a time when an increasing fraction of students wanted to take their classes, so their departments were hiring rapidly.

Imagine what that would have felt like. It was a turbulent time in America but there were lots of like-minded new professors all around them. Students were clamoring to take their classes, and there were long waitlists. They must have felt on top of a swiftly changing world.

But then, the students stopped coming to class. There was a sharp decline in demand for humanities (and some social sciences) through the 70s and early 80s. But the professors hired during the upswing were already permanently tenured. That would lead to an oversupply of expertise in humanities (and some social sciences), a lull in hiring in those departments, and declining enrollments in those classes.

The administration (The Man) told those departments that they couldn’t hire any more like-minded new professors. The Man’s obstinance and backwards-thinking persisted for a decade. The now early-middle-aged humanities (and social science) professors may have felt jilted by both the students and the Man, and were probably bored of teaching smaller and smaller classes, so they decided to join the administration to change things from the inside. Notable to me: three of the four longest serving members of my faculty became administrators, two as Deans of Faculty, one as Dean of Summer School, and two as Interim President of the College.

And it worked! They changed the system! The students started majoring in humanities (and some social sciences) again. The rebound in demand persisted for 20 years. All was well with the liberal arts.

But then the financial crisis happened and demand for humanities (and some social sciences) tanked again. That same mismatch between the supply of teaching expertise and demand for classes taught emerged again. This time, though, adjuncts were a thing. And they were darned tempting. Colleges were already paying through the nose for professors in overstocked departments, both because there were too many of them relative to demand AND because some of them retained their administrator salaries.

Did you know that? I was shocked when someone told me. When professors were promoted into administrative roles they got a raise (fine), but when they stepped down from the position of Dean of the Faculty or Interim President, they KEPT THE RAISE (whoa!). They didn’t go back to just a professor’s salary. That’s why on many liberal arts college tax returns, you’ll find that a few of the highest paid people are current professors, former administrators. Wild, right? (Ok, full disclosure, I haven’t had anyone officially confirm that all former administrators kept their raises when they returned to the faculty, but it’s consistent with the tax return data so I believe it.)

Back to 2009. Demand for humanities classes is tanking, but humanities professors are oversupplied in general and with expensive former administrators in particular. Welcome, adjuncts.

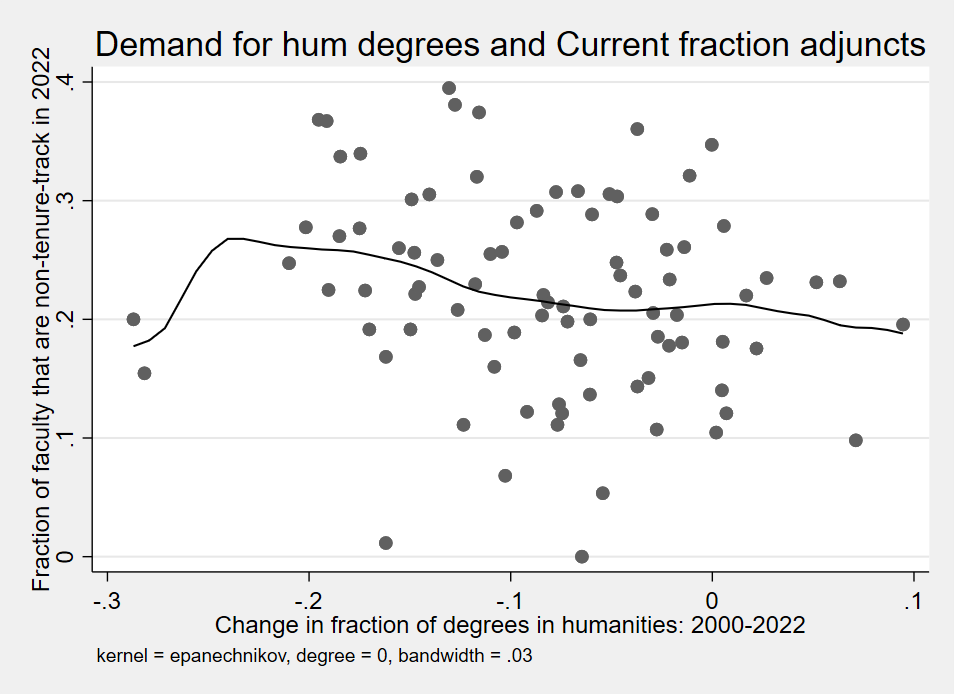

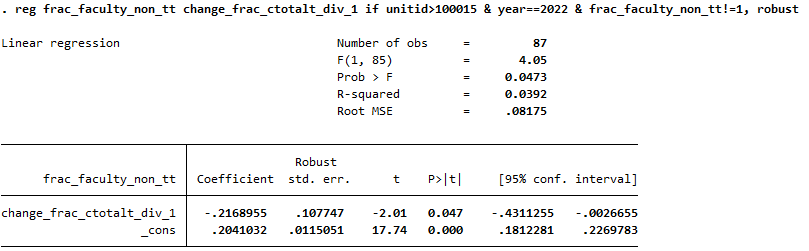

We can see this story in the data. The plot below shows the change in the fraction of degrees awarded in the humanities over the last 20 years on the x-axis and the fraction of faculty that are on temporary contracts now on the y-axis. There’s one dot per school in my dataset and a smoothed line showing the relationship between the variables across the industry. The line is downward sloping, meaning that schools that experienced a larger negative shock to demand for humanities degrees (toward the left side of the figure) have more adjuncts today (toward the top of the figure), while schools that had smaller changes in demand (the righthand side) have fewer adjuncts today (the bottom of the figure).

Yes, this relationship is statistically significant.4 But remember that correlation is not the same as causation and this post is far far away from the kind of evidence that would be published in a good peer-reviewed journal. I still think descriptive patterns are interesting and can be inspiration for more formal research, but, you do you.

The decline in demand for humanities degrees might explain at least some of the trend towards “adjuntification.” What about the leftward lean of administrators? I was telling just-so stories about humanities professors becoming administrators in the 80s and 90s. Can I back any of that up with recent data?

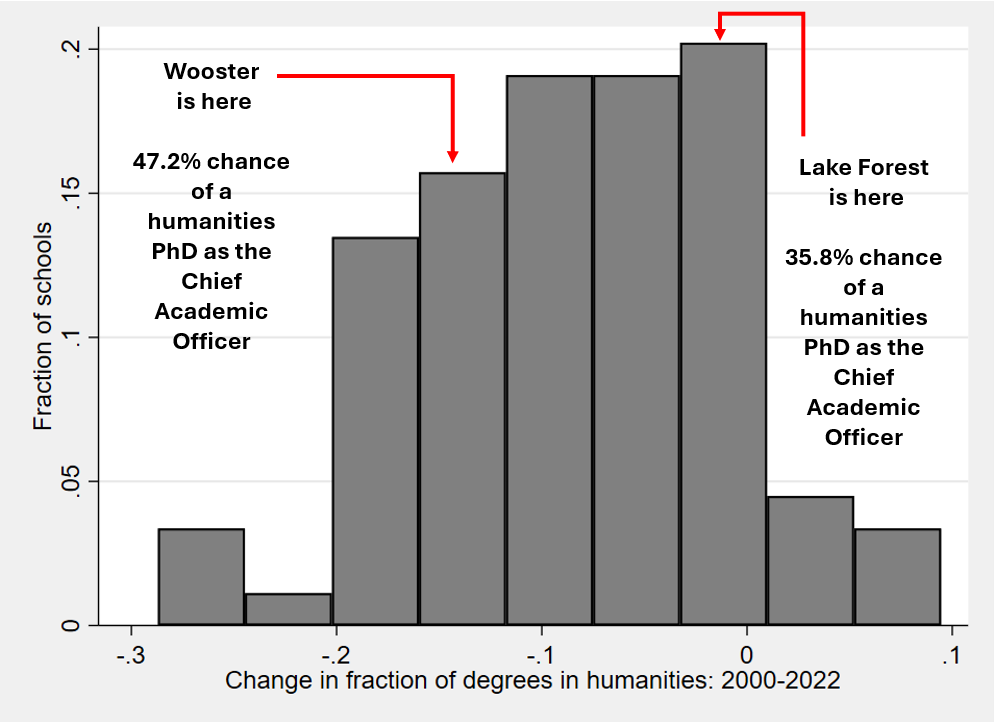

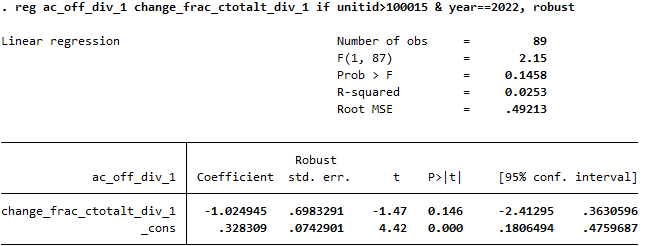

Remember that I tallied the home departments of all the current Chief Academic Officers of the top 100 liberal arts colleges? It turns out that schools that experienced larger shocks to demand in the most recent humanities crisis are more likely to have a humanities professor as their Chief Academic Officer today.

The College of Wooster experienced a 14.5 percentage point drop in humanities majors from 2000-2022. They’re at the 25th percentile of the distribution, meaning that 25-ish schools had demand shocks that were more negative and 75-ish schools had demand shocks that were less negative. Wooster’s Chief Academic Officer is a Professor of French and Francophone Studies. Schools in this range of demand shock have a 47.2% chance of having a humanities professor as their Chief Academic Officer.

By contrast, Lake Forest College had only a 2.9 percentage point drop in humanities majors. They’re at the 75th percentile of the distribution, meaning that 75-ish schools had demand shocks that were more negative and 25-ish had shocks that were less negative. Lake Forest’s Chief Academic Officer is an Economist. Schools in this range of demand shock have a 35.8% chance of having a humanities professor as their Chief Academic Officer.

The relationship between the decline in humanities degrees and the field of the current Chief Academic Officer is not statistically significant.5 It is also a descriptive (correlational) finding and should not be considered causal. I still think the direction the relationship and its magnitude are interesting, but please do take this finding for what it is and contextualize it with other information appropriately.

This post is more speculative than some of my others. It’s economic story-telling, which is kind of humanities adjacent. (Ha. That’s funny.) I hope it illustrates how broad market forces can affect several aspects of an industry and why we should be wary of interpreting any element in isolation.

That’s why I’m writing this Substack. I think in order to understand the whole, you’ve got to look at all the pieces. That’s what I’m looking into, and what I hope to offer you.

Subscribe more for more later.

A few weeks ago I told you that I can’t show plots of salaries for assistant (tenure track professor) and temporary (visiting/lecturer/adjunct) professors because they’re all lumped in one category in IPEDS. In the IPEDS salary datasets (SAL-IS = Salaries for Instructional Staff), that’s true. But IPEDS also shows counts of employees in different roles in a different dataset (EAP = Employees by Assigned Position), and that dataset does split out permanent (tenure-track) from temporary (visiting/lecturer/adjunct) professors. So I can show you numbers of adjuncts, but not anything about the money spent on them.

Fun story: In Colorado now, registered Independents can vote in and are automatically mailed both the Democrat and Republican primary ballots. My city goes Team Red in almost every general election, so I vote in the Republican primary to express some tiny influence in local politics. This is a relatively new rule though, so when I moved here almost ten years ago, I registered as a Republican. I was the 1 Republican to 5.5 Democrats in economics!

Note that this regression (and the one that follows) have fewer than 100 observations. That’s happening for 3 reasons: 1) I’ve dropped a few schools from the dataset because their data in some area is really wacky in basic areas so I don’t trust them (Bryn Marr in revenues, Antioch in expenditures, Wellesley in staffing); 2) Some schools oddly report that 100% of their degrees are now and forever have been awarded in humanities, or they’re missing data on their degrees awarded entirely (College of the Atlantic, Hillsdale, Sarah Lawrence, Soka University, St. John’s, and Thomas Aquinas); 3) Some schools even more oddly report that all of their faculty are not tenure track (Bennington, College of the Atlantic, Principia, and Thomas Aquinas). I may be adding to my list of “not data trustworthy” schools.

"Some schools oddly report that 100% of their degrees are now and forever have been awarded in humanities, or they’re missing data on their degrees awarded entirely (College of the Atlantic, Hillsdale, Sarah Lawrence, Soka University, St. John’s, and Thomas Aquinas)"

We don't have majors at Soka, so perhaps there is some issue there in reporting the data.

I like the post because it takes on some big questions and isn't afraid to speculate as to possible reasons, but I will admit that I am unconvinced by the central argument of this article. At its core, the underlying argument seems to be that the reason the average person perceives universities as being too left-leaning is that they are helmed by administrators who were humanities professors, hired in the 1960s and 1970s, and because humanities professors are overwhelmingly left-leaning, universities tend to be perceived as left-leaning as well. But I think that explanation misdiagnoses the issue.

The real reason in my view why academia is perceived as left-leaning is because of the orientation of the faculty members themselves – something you point out in your post itself. The facts re: the D-R split among faculty members are quite well-known and even if the average person on the street doesn't know those specific numbers, I would speculate that they have a good intuition for that based on their experiences. For example, they see the views being expressed by faculty routinely on issues of public import. And here there's an asymmetry; it is much more likely that after a mass shooting for instance, journalists will reach out to criminologists or sociologists rather than physicists or biologists and the partisan lean among social scientists, not to mention the humanities, is off-kilter relative to those in the hard sciences. Or for example, they can see lots of faculty members protesting alongside their students calling for divestment from Israel or calling for a ceasefire, with only a small handful of faculty members taking the other side of the issue. And it is precisely for reasons like those why the average person on the street perceives academia as being overwhelmingly left-leaning.

Separately, I also speculate that being an administrator moves one more to the center. It is easy to pontificate when there are few real consequences of that pontification but when one is in a role when one is making decisions about budgets, staffing, and the like, it forces one, even left-leaning humanities professors, to take on a more rational and pragmatic orientation than otherwise. I do not know of humanities professors who have gone on to become administrators from personal experience, but I have seen business school faculty members in senior administrative roles and they have all been pragmatic and rational to a fault – maybe even more so than when they were not administrators, but “merely” faculty members in their respective departments.

Personally – and I digress here a bit – the imbalance in partisan lean among faculty is a real tragedy. We talk about demographic imbalances to no end but no one ever wonders why in a discipline like sociology, it is OK to have 43 liberals for every 1 conservative. Would the conservative perspective not have something useful to say regarding the structure of the family? Or about topics such as groups, mobs, and what converts one to the other? And likewise, even as roughly 2/5th of the American public tends to be pro-life (https://news.gallup.com/poll/1576/abortion.aspx), it is hard to imagine very many faculty members holding such views. That is something which all of us – within academia – and those of us outside academia should consider and work to ameliorate.